Mostrar mensagens com a etiqueta ulwick. Mostrar todas as mensagens

Mostrar mensagens com a etiqueta ulwick. Mostrar todas as mensagens

segunda-feira, janeiro 09, 2017

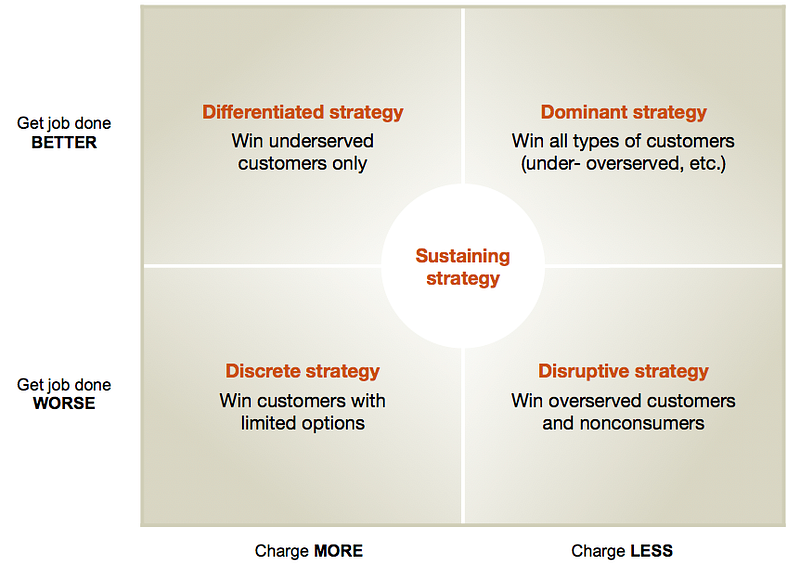

Estratégias ajustadas e desajustadas

A leitura de "The Jobs-to-be-Done Growth Strategy Matrix" fez-me voltar a encontrar esta figura:

Que tinha descoberto e referido em "JTBD e estratégia".

O reencontro com a figura fez-me pensar em várias conversas da semana passada:

Os jornais e os media tradicionais em geral, acossados pelos "chineses" da internet, responderam de forma errada querendo actuar como disruptores quando deviam ter apostado na diferenciação para servir os clientes underserved que continuariam a comprar jornais com melhores conteúdos.

O sector do leite protesta contra as importações de leite. O leite importado para Portugal é mais caro que o leite exportado de Portugal, sinal de que os compradores nacionais desse leite importado não encontram cá certos tipos de leite para o qual o preço não é o mais importante.

Muitas mercearias morreram ao longo das últimas duas décadas porque não se definiram, em vez de competir pelo preço com os "chineses" dos hipermercados, podiam ter optado pela diferenciação e especialização ou pela proximidade e relação.

Já o calçado português, incapaz de competir com os chineses genuínos salvou-se optando por estratégias baseadas na diferenciação (moda por exemplo) ou na proximidade/flexibilidade.

Que outros exemplos acrescentaria?

Que tinha descoberto e referido em "JTBD e estratégia".

O reencontro com a figura fez-me pensar em várias conversas da semana passada:

Os jornais e os media tradicionais em geral, acossados pelos "chineses" da internet, responderam de forma errada querendo actuar como disruptores quando deviam ter apostado na diferenciação para servir os clientes underserved que continuariam a comprar jornais com melhores conteúdos.

O sector do leite protesta contra as importações de leite. O leite importado para Portugal é mais caro que o leite exportado de Portugal, sinal de que os compradores nacionais desse leite importado não encontram cá certos tipos de leite para o qual o preço não é o mais importante.

Muitas mercearias morreram ao longo das últimas duas décadas porque não se definiram, em vez de competir pelo preço com os "chineses" dos hipermercados, podiam ter optado pela diferenciação e especialização ou pela proximidade e relação.

Já o calçado português, incapaz de competir com os chineses genuínos salvou-se optando por estratégias baseadas na diferenciação (moda por exemplo) ou na proximidade/flexibilidade.

Que outros exemplos acrescentaria?

sexta-feira, dezembro 02, 2016

JTBD e estratégia

Um interessante artigo de Ulwick, "The Jobs-to-be-Done Growth Strategy Matrix” by Anthony Ulwick"

"The growth strategies introduced in this framework are defined as follows:

.

Differentiated strategy. A company pursues a differentiated strategy when it discovers and targets a population of underserved consumers with a new product or service offering that gets a job (or multiple jobs) done significantly better, but at a significantly higher price.

...

Dominant strategy. A company pursues a dominant strategy when it targets all consumers in a market with a new product or service offering that gets a job done significantly better and for significantly less money.

...

Disruptive strategy. A company pursues a disruptive strategy when it discovers and targets a population of overserved customers or nonconsumers with a new product or service offering that enables them to get a job done more cheaply, but not as well as competing solutions.

...

Discrete strategy. A company pursues a discrete strategy when it targets a population of “restricted” customers with a product that gets the job done worse, yet costs more. This strategy can work in situations where customers are legally, physically, emotionally, or otherwise restricted in how they can get a job done.

...

Sustaining strategy. A company pursues a sustaining strategy when it introduces a new product or service offering that gets the job done only slightly better and/or slightly cheaper."

quarta-feira, setembro 14, 2016

Apontar aos segmentos e necessidades underserved (parte II)

Parte I.

"An effective market strategy should align the strengths of a company’s product offerings with the customer’s unmet needs.

...

Decide what offerings to target at each outcome-based segment.

The first step in defining the market strategy is to determine which products to target at each of the outcome-based segments that have been discovered.

...

Communicate the strengths of those products to customers in the target segment...

Knowing that a product has features that are a competitive strength in a segment of the market is an important insight when it comes to aligning a product portfolio with customer needs.

...

Include an outcome-based value proposition in those communications...

Build an AdWords campaign around unmet needs [Moi ici: Ainda ontem numa PME discutimos esta realidade. Eu sei lá que empresas texturizam moldes, eu preciso de texturizar um molde, primeiro vem o "job". Depois, é que aparece o nome dos potenciais fornecedores]

...

Assign leads to ODI-based segments...

determine which outcome-based segment a specific prospect belongs to. With this insight, the prospect can be guided toward the solution that will best address their underserved outcomes.

.

Arm the sales team with effective sales tools

Lastly, the sales team can be taught how to identify what outcome-based segment a customer or prospect belongs to and guide the conversation accordingly. Approaching a customer with the right value proposition and a clear understanding of their situation and unmet needs goes a long way to building credibility."

sexta-feira, agosto 30, 2013

Foco no cliente, não na oferta

O livro "Service Innovation" de Lance Bettencourt começa muito bem:

"'The secret of true service innovation is that you must shift the focus away from the service solution and back to the customer. Rather than asking, "How are we doing?" a company must ask, "How is the customer doing?" To achieve this shift in focus, companies must begin to think very differently about how customers define value based on the needs they are trying to satisfy. A proper understanding of these needs enables value to be understood in advance of any particular innovation being created. True service innovation demands that a company expands its horizon beyond existing services and service capabilities and give its attention to the jobs that customers are trying to get done and the outcomes that they use to measure success in completing those jobs."Algo bem na linha do que MacDivitt e Wilkinson escrevem em "Value-Based Pricing":

"Arguably the biggest challenge faking companies at the beginning of their journey was to identify the competitive advantage (or advantages) that were to form their vehicle for VBP. This is a rather scary and quite subtle consequence of a cost-based approach. Intense focus on specification and functionality of products, coupled with a search for a competitive advantage, leads almost inevitably to technological development of some aspect of the specification the seller considers to be important.

.

Companies have a good microscope but are using it to look at the wrong thing. If and when a differentiation is found, it is almost certain to be product-based. As time goes on, this becomes harder and harder to do regardless of how much money is spent. Focusing exclusively on product innovation, and spending all their effort and development funds on this, prevents companies from looking in the right direction - namely, understanding what value the customer is looking for.

...

The issue is not the product—it is the total offer that matters. Delivery, technical support, laboratory tests, assays, and so on are all seen through the lens of helping to sell the (more or less commoditized) product and not as value-adding elements in their own right. This is where the problem lies. Sellers often consider themselves to be scientists first and salespeople (a long way) second. While sellers can understand the arguments about the total offer, their training and education take them back inexorably to discussions of product technology. Since they are selling on the basis of product specification, they can do nothing else but cave in when a buyer demands a discount on the basis that the product in question is a commodity. This is demoralizing for this kind of salesperson because she can see no way out."

Entretanto, Ulwick e Bettencourt em "Giving Customers a Fair Hearing" sistematizam estas estruturas para abordar o cliente:

quarta-feira, junho 06, 2012

Perceber o que está a acontecer aos seus clientes?

Anthony Ulwick em "What Customers Want" usa este esquema para estudar e identificar oportunidades de negócio.

O que é que acontece à posição competitiva de um fornecedor pioneiro com um bom produto/serviço à medida que os anos passam?.

À medida que os anos passam, o produto/serviço amadurece, passa a ser mais conhecido pelos seus clientes, passa a fazer parte da rotina dos clientes e, com a chegada de concorrentes começa a sua progressiva banalização.

.

À medida que os anos passam, três tipos de clientes emergem:

- o cliente A que está satisfeito com o produto que recebe e que até é capaz de pensar que o produto é bom demais para as suas reais necessidades, até preferia um produto mais simples, sem grande complicação (às vezes, esta opinião é resultado da incapacidade do fornecedor "educar" estes clientes para o valor extra que podem co-criar com a sua oferta);

- o cliente B que evoluiu no seu negócio e necessidade e, que sente que o produto que recebe já não está à altura das suas expectativas

- o cliente C que está satisfeito com o produto e que o acha realmente aquilo que melhor se adequa às suas necessidades.

Ou seja, para o fornecedor parece que tudo está OK, o produto que sempre foi oferecido continua a ser entregue e a cumprir as especificações. No entanto, o mercado está numa situação instável, maduro para uma reconfiguração. A quota de mercado deste fornecedor pode ser atacada por duas vias:

- cliente A - os clientes do tipo A sentem que estão a receber um produto sobre-dimensionado para as suas necessidades, sentem-se sobre-servidos. Estão maduros para uma entrada disruptora, estão maduros para abraçar um novo fornecedor que lhes ofereça um produto mais simples, mais básico, mais barato.

- cliente B - os clientes do tipo B sentem que estão a receber um produto sub-dimensionado para as suas necessidades, sentem-se sub-servidos. Estão maduros para abraçar um fornecedor que lhe ofereça um produto superior, um produto mais adequado às suas necessidades crescentemente exigentes.

Ás vezes, basta uma crise económica para precipitar as coisas, subitamente, parece que o mundo do fornecedor é atacado de todos os lados:

- concorrentes atacam a fatia dos clientes do tipo A, oferecendo-lhes produtos básicos e muito mas baratos;

- concorrentes atacam a fatia dos clientes do tipo B, oferecendo-lhes produtos mais completos e capazes de proporcionar uma maior co-criação de valor.

Quantas vezes é que o fornecedor percebe o que está a acontecer? Quantas vezes o fornecedor baixa o preço sem mexer no produto e pensando que tudo se resume ao preço?

.

.

Quantas vezes o fornecedor usa uma mesma resposta para recuperar ambos os tipos de clientes?

.

Reduzir salários para reduzir o preço e seduzir os clientes do tipo B para os recuperar... pois.

.

Acrescentar atributos para seduzir os clientes do tipo A para os recuperar... pois.

.

Reduzir salários para reduzir o preço e seduzir os clientes do tipo B para os recuperar... pois.

.

Acrescentar atributos para seduzir os clientes do tipo A para os recuperar... pois.

quinta-feira, abril 19, 2012

Diferentes clientes valorizam diferentes experiências (parte IV)

Parte I, parte II, parte III.

.

Situação 3: Imaginem uma pessoa com alguma idade que decide comprar uma bicicleta para fazer algum exercício ao fim-de-semana, passeando numa qualquer marginal. O que pode influenciar a decisão de escolher uma determinada bicicleta?

Situação 4: Imaginem uma pessoa com uma paixão pelo cicloturismo e que acaba de ingressar num clube de entusiastas da modalidade que organiza passeios e provas com alguma regularidade. O que pode influenciar a decisão de escolher uma determinada bicicleta?

Ponham-se agora na posição de quem vai abrir uma loja para vender bicicletas. Será que uma loja preparada para servir os clientes que se enquadram na situação 3 é a mais adequada para servir igualmente os clientes que se enquadram na situação 4? O que é que cada tipo de cliente espera encontrar na loja além da bicicleta?

.

Este desafio parece não ser tão drástico como o dos restaurantes. É possível ter uma loja que sirva simultaneamente os clientes da situação 3 e da situação 4. Mas quem é que fica melhor servido? E quem fica prejudicado?

Escolher um grupo, e por grupo não falo de rótulos exteriores, e identificar as experiências que os clientes procuram e valorizam (importância) e, depois, avaliar a oferta actual, até que ponto a oferta actual consegue satisfazê-los? E, assim, conseguem-se identificar os mercados "overserved" e "underserved".

.

Continua, com os mercados "overserved", palco das inovações disruptivas e, depois, com a ligação dos grupos e suas experiências ao desempenho relativo no mercado.

.

Situação 3: Imaginem uma pessoa com alguma idade que decide comprar uma bicicleta para fazer algum exercício ao fim-de-semana, passeando numa qualquer marginal. O que pode influenciar a decisão de escolher uma determinada bicicleta?

Situação 4: Imaginem uma pessoa com uma paixão pelo cicloturismo e que acaba de ingressar num clube de entusiastas da modalidade que organiza passeios e provas com alguma regularidade. O que pode influenciar a decisão de escolher uma determinada bicicleta?

Ponham-se agora na posição de quem vai abrir uma loja para vender bicicletas. Será que uma loja preparada para servir os clientes que se enquadram na situação 3 é a mais adequada para servir igualmente os clientes que se enquadram na situação 4? O que é que cada tipo de cliente espera encontrar na loja além da bicicleta?

.

Este desafio parece não ser tão drástico como o dos restaurantes. É possível ter uma loja que sirva simultaneamente os clientes da situação 3 e da situação 4. Mas quem é que fica melhor servido? E quem fica prejudicado?

.

Gail McGovern e YoungmeMoon em "Companies and the Customers Who Hate Them" referem o que acontece a uma loja, por exemplo, que não se define e quer servir vários tipos de clientes... como tem de vender, o lojista deixa de ser um consultor de compra e passa a ser um vendedor, facilmente se entra no terreno de areias movediças, ou na zona escorregadia em que facilmente se acaba a vender algo que não é o mais adequado à realidade da vida de um cliente:

"Companies can profit from customers’ confusion, ignorance, and poor decision making in two related ways. The first evolves out of the legitimate attempt to create value by giving customers a broad set of offerings. The second emerges from the equally legitimate decision to use fees and penalties to cover costs and discourage undesirable customer behavior.Ponham-se agora na posição de quem vai abrir uma unidade de montagem de bicicletas. Será que uma unidade preparada para servir os clientes que se enquadram na situação 3 é a mais adequada para servir igualmente os clientes que se enquadram na situação 4? E se pensarmos em carros? E se pensarmos em sapatos de ténis? E se pensarmos em comida para cães?

In the first case, a company creates a diverse product and pricing portfolio to offer various value propositions to different customer segments. All else being equal, a hotel that has three types of rooms at three price points can serve a wider customer base than a hotel that has just one type of room at one price. However, customers benefit from such diversity only when they are guided toward the offering that best suits their needs. A company is less likely to help customers make good choices if it knows that it can generate more profits when they make poor ones.

Of course, only the most flagrant companies would explicitly seduce customers into making bad choices. Yet there are subtle ways in which even generally well-intentioned firms use complex portfolios to encourage suboptimal choices—tactics that hasten the descent down the slippery slope. Complicated offerings can confuse customers with a lack of transparency (hotels, for example, often don’t reveal information about discounts and upgrades); they can make it hard for customers to distinguish among products, even when complete information is available (as is often the case with banking services); and they can take advantage of consumers’ difficulty in predicting their needs (for instance, how many cell phone minutes they’ll use each month).

.

Lembram-se dos dinossauros azuis?

.

Em cada mercado é possível identificar várias situações onde diferentes grupos de clientes valorizam mais ou menos de forma homogénea, diferentes experiências, diferentes "outcomes".

.

Quando se estuda um desses grupos o truque é (trechos de "What Customers Want" de Anthony Ulwick):

"in the outcome-driven paradigm the objective is not to figure out what solutions customers like best, but to figure out where the areas of opportunity lie in a market, that is, to determine which jobs and outcomes are underserved— and, as the formula shows, that can be determined quite easily. ... we are asking how important a certain outcome is and how well that outcome is currently satisfied. ... An opportunity for improvement exists when an important outcome is underserved—that is, when it has a high opportunity score. Such outcomes merit the allocation of time, talent, and resources, as customers will recognize solutions that successfully serve these outcomes to be inventive and valuable. Given that higher opportunity scores represent better opportunities, we have devised the following set of rules:

Reparem na figura e nas suas unidades:

- Outcomes and jobs with opportunity scores greater than 15 represent extreme areas of opportunity that should not be ignored ...

- Outcomes and jobs with opportunity scores between 12 and 15 can be defined as “low-hanging fruit,” ripe for improvement ...

- Outcomes and jobs with opportunity scores between 10 and 12 are worthy of consideration especially when discovered in the broad market. Many such opportunities are commonly revealed even in the most mature markets.

- Outcomes and jobs with opportunity scores below 10 are viewed as unattractive in most markets and offer diminishing returns."

Escolher um grupo, e por grupo não falo de rótulos exteriores, e identificar as experiências que os clientes procuram e valorizam (importância) e, depois, avaliar a oferta actual, até que ponto a oferta actual consegue satisfazê-los? E, assim, conseguem-se identificar os mercados "overserved" e "underserved".

.

Continua, com os mercados "overserved", palco das inovações disruptivas e, depois, com a ligação dos grupos e suas experiências ao desempenho relativo no mercado.

terça-feira, abril 17, 2012

Não se pode ser bom a tudo e para todos (parte II)

Parte I e depois da lição da Tesco.

.

O problema reside na heterogeneidade dos clientes. Os clientes não são todos iguais e, diferentes clientes procuram e valorizam diferentes experiências. E quando uma empresa opta, muitas vezes inconscientemente, por servir um determinado tipo de clientes, está, em simultâneo, a optar por servir menos bem outros tipos de clientes.

.

Antigamente, no tempo em que não éramos todos "weird" e, havia muitas barreiras sociais a ser-se e assumir-se "weird", as empresas podiam dar-se ao luxo de desenvolver um produto/serviço dedicado a servir o grande grupo de clientes normais. Hoje, agora que somos todos "weird", e há mais gente fora da caixa do que dentro da caixa, é cada vez mais difícil ter um produto/serviço, ter uma empresa, ter um modelo de negócio que sirva para mais do que um tipo de cliente em simultâneo.

.

O que cada empresa e cada potencial cliente têm de fazer é tentarem-se encontrar. Uma empresa não pode ser boa a tudo e para todos em simultâneo.

.

Um exemplo:

.

Situação 1: Imaginem uma pessoa que trabalha no centro de uma cidade, no escritório de uma empresa, e que tem uma hora para almoçar. O que pode influenciar a decisão de escolher onde almoçar?

"a company must have captured the customer inputs already and must now determine which of those jobs, outcomes, and constraints are most underserved and represent solid opportunities for improvement and which are most overserved and represent unique opportunities for cost reduction and possible disruption....

"In the outcome-driven paradigm, an opportunity for growth is defined as an outcome, job, or constraint that is underserved. An underserved outcome, in turn, can be defined as something customers want to achieve but are unable to achieve satisfactorily, given the tools currently available to them. These underserved outcomes point to where customers want to see improvements made and where they would recognize the delivery of additional value."...

"We find that most managers agree that an outcome that is both important and unsatisfied represents a solid opportunity for improvement and that addressing it successfully would result in a valued product or service. The best opportunities, then, spring from those desired outcomes that are important to a customer but are not satisfied by existing products and services."Mas por que raio é que uma empresa que sabe que precisa de clientes satisfeitos, para poder aspirar a ter resultados financeiros decentes, não os consegue satisfazer?

.

O problema reside na heterogeneidade dos clientes. Os clientes não são todos iguais e, diferentes clientes procuram e valorizam diferentes experiências. E quando uma empresa opta, muitas vezes inconscientemente, por servir um determinado tipo de clientes, está, em simultâneo, a optar por servir menos bem outros tipos de clientes.

.

Antigamente, no tempo em que não éramos todos "weird" e, havia muitas barreiras sociais a ser-se e assumir-se "weird", as empresas podiam dar-se ao luxo de desenvolver um produto/serviço dedicado a servir o grande grupo de clientes normais. Hoje, agora que somos todos "weird", e há mais gente fora da caixa do que dentro da caixa, é cada vez mais difícil ter um produto/serviço, ter uma empresa, ter um modelo de negócio que sirva para mais do que um tipo de cliente em simultâneo.

.

O que cada empresa e cada potencial cliente têm de fazer é tentarem-se encontrar. Uma empresa não pode ser boa a tudo e para todos em simultâneo.

.

Um exemplo:

.

Situação 1: Imaginem uma pessoa que trabalha no centro de uma cidade, no escritório de uma empresa, e que tem uma hora para almoçar. O que pode influenciar a decisão de escolher onde almoçar?

Situação 2: Imaginem uma pessoa que trabalha numa empresa, que ocupa uma posição de decisão e que aproveita a hora do almoço, para realizar reuniões, negociar com parceiros e receber clientes. O que pode influenciar a decisão de escolher onde almoçar?

Ponham-se agora na posição de quem vai abrir um restaurante para servir almoços.

.

Será que um restaurante adequado para servir os clientes que se enquadram na situação 1, também é o adequado para servir, em simultâneo, os clientes que se encontram na situação 2? Porquê?

.

Quase tudo o que contribui para a escolha de um cliente na situação 1 é irrelevante para a decisão de preferência de um cliente na situação 2. E mais, muito do que contribui para a escolha de um cliente na situação 2 prejudica os factores que ditam a preferência de um cliente na situação 1.

.

Ser bom em simultâneo nas situações 1 e 2 é difícil e, quanto mais especializada for a concorrência, mais difícil é misturar tudo no mesmo espaço servido pelos mesmos recursos e, dedicado a clientes que procuram e valorizam experiências diferentes.

.

E a sua empresa… e o sector em que opera a sua empresa, quantas situações diferentes consegue imaginar? E que situações é que a sua empresa elegeu como alvo para servir? Seja qual for a sua escolha, os meus parabéns!!! A maioria das empresas não faz escolhas!

.

A maioria das empresas acha um pecado dizer não a um potencial cliente que não se encaixa num certo perfil. E, com isso, alguém vai sair prejudicado, muitas vezes é a empresa, não o cliente, que perde dinheiro ao decidir servir esses outros tipos de clientes. Outras vezes, muitas vezes, são os clientes que ficam com uma sensação de desconforto, que ficam com o sentimento de que não estão a ser bem servidos.

.

Trecho retirado de "What Customers Want" de Anthony Ulwick.

Continua.

quinta-feira, abril 12, 2012

Companies must become outcome-driven (parte I)

“For a company to innovate, it must create products and services that let consumers perform a job faster, better, more conveniently, and/or less expensively than before. To achieve this objective, companies must know what outcomes customers are trying to achieve (what metrics they use to determine how well a job is getting done) and figure out which technologies, products, and features will best satisfy the important outcomes that are currently underserved.Gosto desta abordagem dos "jobs-to-be-done" que os clientes têm de realizar para conseguir obter, viver, os resultados, as experiências (outcomes) pretendidas.

…

when capturing customer requirements, managers must be looking for the criteria customers use to measure the value of a product or service—not their ideas about the product or service itself.

…

being customer-driven is just not good enough to ensure success—companies must become outcome-driven.

…

To execute their innovation processes successfully, companies must obtain three distinct types of data. They must know which jobs their customers are trying to get done (that is, the tasks or activities customers are trying to carry out); the outcomes customers are trying to achieve (that is, the metrics customers use to define the successful execution of a job); and the constraints that may prevent customers from adopting or using a new product or service.

…

In both new and established markets, customers (people and companies) have jobs that arise regularly and need to get done. To get the job done, customers seek out helpful products and services.”

.

Trechos retirados de "What Customers Want" de Anthony Ulwick.

terça-feira, abril 10, 2012

Leituras para reflexão

Um conjunto de textos interessantes que merecem ficar no meu arquivo:

.

Outro tema recorrente neste blogue é a tareia ao "eficientismo" acima de tudo, por isso:

- "You better not bake your costs into pricing" - um texto em sintonia com a mensagem deste blogue e em contramão, face à maioria dos economistas, políticos e comentadores (a tríade):

"customers are not paying to offset your costs. They are paying to fulfill their needs –utilitarian or hedonistic. It does not matter to them what your costs are or how you are allocating them. When was the last time you were at a coffee store and paid separately for employee salary or the decorative lighting?Enquanto os membros da tríade só pensam nos custos, este blogue pertence ao clube da minoria que prefere falar do preço, que prefere falar do valor co-criado. Por falar em valor co-criado:

It is not the cost that comes first, it is the price that comes first."

- "What Really Replaces Marketing (Madness).." - texto curto mas cheio de sumo, tenho de exercer uma forte contenção para não o colocar quase todo aqui:

"The bottom line in my thinking is that, since Value is dominantly created in-use and is a result of co-creation between company and Customer, marketing strategies should shift their focus from creating momentum for value exchange (the sale) to creating momentum for interactions that support Customers in creating value for themselves. And since value is something that can only be defined by its beneficiary we need to understand what outcomes Customers desire when they hire a company’s resources to get their jobs done. The Customer’s journey towards that outcome is where opportunity for marketing lies to design service that support Customers, employees and partners to co-create more (or better?) value together.""Service Dominant Logic, Customer Jobs-to-be-Done, Service Design" - BTW, ando a aprender umas coisas muitos interessantes sobre Customer Jobs-to-be-Done com Anthony Ulwick.

.

Outro tema recorrente neste blogue é a tareia ao "eficientismo" acima de tudo, por isso:

- "Wrangling complexity: the service-oriented company" - texto que merecia uma reflexão séria pelos gestores da coisa pública, claro que deliro. Sobretudo, na área da Saúde, ou na área da Justiça, ou na área da Educação, com as suas instituições gigantes, lentas e comandadas a partir de Lisboa:

"Most businesses today are not designed with agility in mind. Their systems are tightly coupled, because their growth has been driven by a desire for efficiency rather than flexibility.

Consider the difference between a car on a road and a train on a train track. The car and the road are loosely coupled, so the car is capable of independent action. It’s more agile. It can do more complex things. The train and track are tightly coupled, highly optimized for a particular purpose and very efficient at moving stuff from here to there – as long as you want to get on and off where the train wants to stop. But the train has fewer options – forward and back. If something is blocking the track, the train can’t just go around it. It’s efficient but not very flexible.

Many business systems are tightly coupled, like trains on a track, in order to maximize control and efficiency. But what the business environment requires today is not efficiency but flexibility. So we have these tightly coupled systems and the rails are not pointing in the right direction. And changing the rails, although we feel it is necessary, is complex and expensive to do. So we sit in these business meetings, setting goals and making our strategic plans, arguing about which way the rails should be pointing, when what we really need is to get off the train altogether and embrace a completely different system and approach."

Subscrever:

Mensagens (Atom)